Archbishop Joseph Thomas Duhamel, a champion of Franco-Ontarian identity

By Marc Aubin

Joseph-Thomas Duhamel (1841-1909) was one of the most influential residents of Ottawa’s Lowertown and Ontario’s French-Canadian history. He was the son of a blacksmith, the youngest of 12, and only two years old when his family came to Ottawa in 1843. Three of his brothers were local butchers. Fully bilingual, Duhamel was ordained a priest in 1863 by Bishop Guigues. He went on to be the longest serving Catholic leader of Ottawa, and likely the most political of all of Ottawa’s archbishops.

The transfer of power to Duhamel after Bishop Guigues’ death in 1874 was not without controversy in the Catholic church hierarchy. Anglophone Catholic bishops in Ontario pressed for the installation of an Anglophone bishop and to have the diocese transferred to Toronto from its home in Quebec City. Guigues had appealed to his Quebec colleagues to appoint a French Canadian, arguing that “French Canadians could never expect to receive from an Irish prelate the fair treatment that a French Canadian would give to his Irish diocesans,” (Dictionary of Canadian Biography). It was Duhamel who would outmaneuver them years later in 1886 by going over their heads and petitioning Pope Leo XIII to raise Ottawa to the status of archdiocese, becoming the first archbishop of the new diocese.

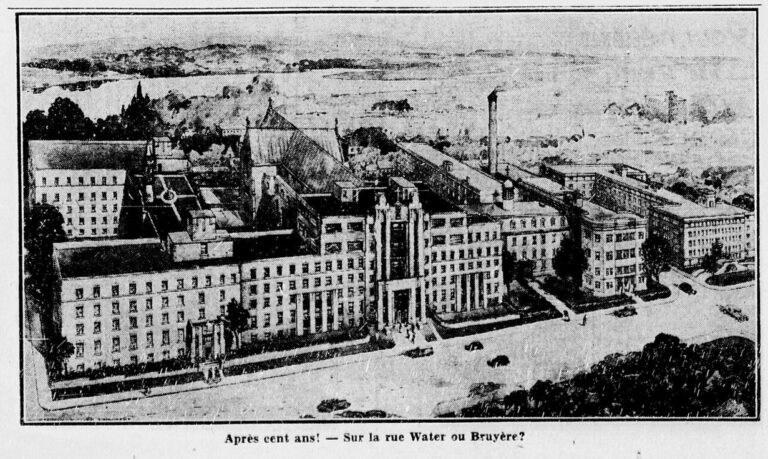

Under Duhamel, Ottawa’s Catholic community still needed to be developed to build on the early foundations laid by Guigues. Ottawa was now the nation’s capital and was experiencing renewed prosperity with the influx of public servants. Duhamel envisioned a Catholic diocese centred around the increasingly magnificent Notre Dame Cathedral that would provide a stronghold of Catholicism in a united French and English Canada. The diocese grew enormously during his tenure as bishop from 1874 to 1886 and as archbishop from 1886 to 1909. Over his time, the number of religious orders serving the community grew from three to 23, and the number of priests from 22 to 114.

Duhamel believed that the clergy needed to be politically involved. He was an especially strong advocate of Catholic education rights, insisting that the children of his diocesans attend Catholic schools and seeking to provide French-speaking Catholics with French-language schools. He encouraged the development of many organizations, including mutual benefit societies, like the Union of Canada. In fact, he was a key person behind the expansion of the Union of Canada to all of Ontario, where there were 150 branches by the time of his death. He used meetings and the organization’s newsletter as a conduit for his influence across Ontario’s Francophone communities.

During his tenure, Duhamel had to manage ongoing infighting between French and Irish Catholics in Ottawa. One of the most influencial of these being his rejection of efforts by Father Fallon at the University of Ottawa to make it an English-only institution. Duhamel preferred that both languages be used for instruction. Fallon left Ottawa and became the Bishop of London, Ontario, from where he waged a very public campaign in support of the provincial government’s efforts to assimilate French-Canadians.

In 1909, on the verge of the Regulation 17 controversy, Duhamel raised the alarm in the Union of Canada’s newsletter, warning Ontario Francophones of the increasingly anti-Francophone provincial government of James Whitney. Instruction in French had progressively been restricted in Ontario in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1912, the Ontario government passed Regulation 17, severely limiting the use of French instruction in schools. The centre of the fight was Ottawa and, more specifically, the Guigues School, where a historic plaque tells some of the story.

By the time of his death, Duhamel had taken Ottawa from a pioneer Catholic diocese to a well-established and independent archdiocese with a flourishing bilingual character. He worked tirelessly for his diocese through a tumultuous period of ethnic conflict. He brought together French Canadians of Ontario, supporting them in the development of institutions that could resist the dominance of Anglo-Protestant Ontarians. As the Dictionary of Canadian Biography states, he “knit together Ontario’s scattered French-Canadian population into a vibrant community, one that was prepared and able to fight for its rights.”

(Photo: Library and Archives Canada)

(Photo: Archives of the Archdiocese of Ottawa-Cornwall)